The coronavirus delta variant

Rise of the “delta” variant of SARS-CoV-2

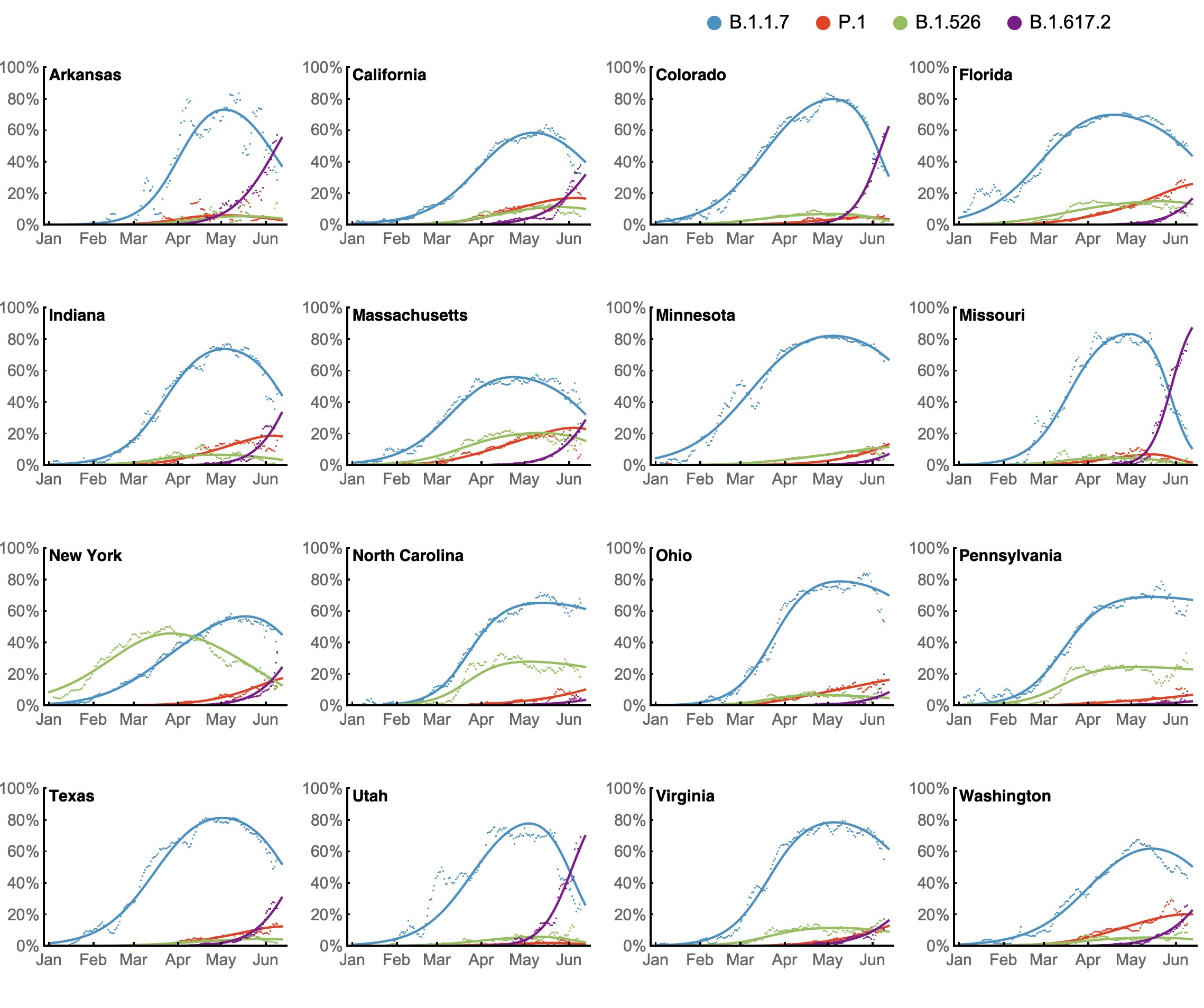

Percent of cases for delta shown in purple

Source: Trevor Bedford of Fred Hutchinson Institute, via Twitter

SARS-CoV-2 Delta and other “variants of concern”

People have been asking me questions about the “delta variant” that’s being discussed widely in the media. There’s quite a bit of good reporting on it, but here’s my summary of key points.

What is a variant?

A variant of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus is a strain of the virus that has a particular pattern of changes in its RNA that makes it a little bit different from the original strain that swept the world. Those changes aren’t necessarily significant to us, but some changes make some variants “of concern.” The World Health Organization now names important variants with Greek letters, such as delta. (Rather than naming them for the place where they were first identified, which is not considered polite any more.)

Where do variants come from?

When a virus infects a cell, it makes copies of itself. Each time the viral RNA is copied, there is a small chance that a mistake will be made and the copy will be slightly different from the original. This is called a mutation. Most of the time, mutations are bad for the virus, or irrelevant. Once in a while, a mutation randomly occurs that gives the virus a survival advantage of some kind. The virus born with this advantage will infect a new cell and make more of the variant virus.

If a particular variant has a significant advantage over the earlier version, that variant will gradually take over as it “wins” the competition for cells. This is called evolution.

Because viruses replicate on a staggering scale—about a thousand copies are made in every cell infected (source)—there are countless opportunities for mutation. Therefore viruses evolve very quickly compared to, say, birds or people.

Is the delta variant more dangerous?

In the case of the “delta” variant, the coronavirus has acquired a combination of random mutations that make it more contagious. That means that in a given situation, a person infected with the delta variant will infect more people than a person infected with an earlier version of SARS-CoV-2.

The delta variant appears to be significantly more contagious. In geographic regions where it appears, it soon becomes the dominant version of the virus circulating in the community.

At this time, I’m not sure if the delta variant makes people sicker. I’m waiting for data to come in. Measuring this can be hard, as many factors determine mortality.

Remember that evolution of the virus favors mutations that increase the number of viruses in the world. Natural selection doesn’t really care about virulence (how sick it makes the host) unless a virus is too deadly for its own good, and kills its hosts too quickly. So over the long term, viruses tend to evolve to be less virulent (milder disease) but more contagious.

For now, people who were at higher (or lower) risk of getting a bad case of COVID-19 from the earlier variants are still at higher (or lower) risk from the delta variant. But their risk of getting COVID at all has gone up.

What if I am vaccinated?

Great news here: the highly effective vaccines from Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson are still highly effective against the delta variant. The mutations in the delta variant don’t seem to disguise it from your immune system. Severe disease or death are rare in vaccinated people.

It’s not entirely clear whether the delta variant is transmitted by vaccinated people–hence the controversy about masking (see below). It certainly is transmitted far less than by unvaccinated people.

What if I am not fully vaccinated, or I am unvaccinated?

With the emergence of the delta variant, your risk of catching COVID-19 goes way up. In particular, if you’ve only had one dose of the two-dose vaccines (Pfizer and Moderna), you are much less protected against delta than against the earlier versions.

In places where a majority of people are not vaccinated, we can expect to see outbreaks and rising case numbers from the delta variant. In places where enough people have been vaccinated to give herd immunity, transmission of all variants will better controlled.

What are the implications for public health?

See image above—purple line is fraction of COVID cases from the delta variant. It’s “taking over” in many places in the US. It’s now 95% of all new cases in the UK.

In places where the delta variant is spreading fast (as of July 2, 2021, that would be Missouri, Arkansas, Nevada, Utah, and many local areas such as Los Angeles) we are likely to see an increase in cases after a sharp and steady decline in recent months.

These delta variant cases will be heavy-majority in unvaccinated or partially vaccinated people, but there will also be some breakthrough cases among the vaccinated.

The biggest implication for Americans is this: Ongoing community spread of SARS-CoV-2, any variant, for any reason, gives more opportunities for the virus to evolve as I described above. More infections = more mutations = more chances for an even more infectious variant to emerge. Worst case scenario would be the evolution of a variant that evades the immune system of vaccinated people, making our fabulous vaccines obsolete. This is why it’s important to minimize community spread even if deaths are very low. (Another reason why refusing the vaccine is not only a personal choice, but a choice with consequences for other people.)

Globally, the story is different. The delta variant is wreaking havoc in Africa and other regions where vaccination rates are very low. This variant spreads with brief, casual contact. Many, many people are going to die because they did not have access to a vaccine before delta hit.

What about masks?

The CDC says fully vaccinated people don’t need masks to protect themselves or others in most situations. The WHO says because the delta variant is so contagious, everyone should mask up.

The reality in the US is, most adults who have refused the vaccine are not going to wear a mask either. This population with the highest risk for transmitting the delta variant isn’t going to comply, so I think the discussion is sort of pointless.

Also, the WHO mask recommendation is for the whole world, not just the US. In many countries the vaccines in use (such as the Chinese-made Sinovac) are not as effective as the ones approved in the US. If such places also have a delta surge, masking for everyone makes sense.

What about treatment for the delta variant?

In general, treating people sick from delta COVID is the same as any variant. One exception: Several monoclonal antibody therapies have been approved for COVID patients, but this type of treatment may be very sensitive to the variant. A couple of the monoclonals have been shown to be ineffective against one variant so far (source).

CDC page on coronavirus variants https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/variant-info.html

Extra for the scholars:

Why do the vaccines still work but antibody therapy might not?

All the coronavirus vaccines currently in use in the US immunize against the “spike” protein, a complex 3D molecule found on the surface of the virus. Vaccinated people naturally make antibodies against many different bits of the spike protein. These are called “polyclonal” antibodies, as opposed to “monoclonal” antibodies which are against only one bit of the spike (mono = one; poly = many). Think of the story of the blind men describing an elephant: the elephant is like the spike protein, and each blind man is like an antibody.

If a variant virus has a random mutation in the bit of the spike protein that the monoclonal antibody binds to, then that antibody therapy might not work anymore. In an immunized person, however, other antibodies to other bits of the spike protein are still available.

If you can get through the paywall, here’s an excellent article about the variants in The Economist

Have you been vaccinated yet? Every American age 12 and up is now eligible.

In California, visit https://myturn.ca.gov/ to find appointments for a FREE vaccine near you.

Amy Rogers, MD, PhD, is a Harvard-educated scientist, novelist, journalist, and educator. Learn more about Amy’s science thriller novels, or download a free ebook on the scientific backstory of SARS-CoV-2 and emerging infections, at AmyRogers.com.