Advance Care Planning in time of pandemic

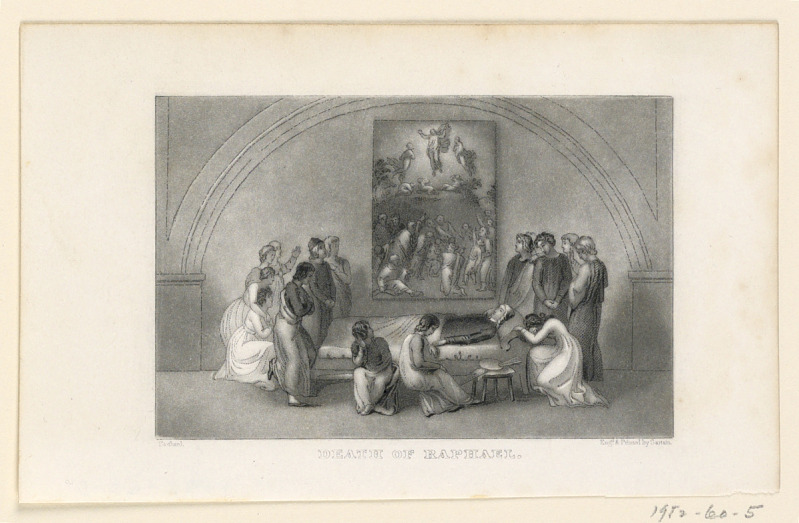

Death of Raphael, Engraver John Sartain, American, 1808–1897. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Open access.

Early in the pandemic, a reader suggested that I write something about advance directives. I agreed this was an important topic, but in the vortex of fear and rapid change of March/April I didn’t feel like it was the time. Today I read a sad article in the Washington Post about COVID-19 patients who survive to get off a ventilator but linger in a coma for long periods of time. Some of them continue to suffer major neurologic deficits thereafter. While this is not common, with the number of people who will probably be infected by SARS-CoV-2, even rare events will add up to a substantial number of individuals.

In my writing about the coronavirus pandemic, I’m trying to maintain a balance between the facts of what this virus will do (probably kill a million Americans, eventually) and a sense that although this is a big number, it’s a small percentage. Therefore your personal chance of death or disability may be quite low especially if you’re in a low-risk demographic. We should all be honest and respectful of the virus’s power, but also not paralyzed by fear.

With that in mind, today I suggest that the pandemic should prompt you to look at your end of life plan. With COVID-19 sending people suddenly into intensive care, families and health care providers are facing questions about what medical interventions the patient would want. Don’t leave that difficult decision-making process to chance. Have you formally prepared advance care planning documents? If so, confirm that those documents accurately reflect your current thinking. If not, you should right now start the process to create them.

What is Advance Care Planning?

This lengthy document titled Advance Care Planning: Healthcare Directives, from the NIH’s National Institute on Aging is a wonderful, comprehensive summary in readable language. I’ll highlight a couple of key points.

Advance care planning or advance directives are legal documents that tell your relatives and your doctors what types of medical interventions you do or do not want in a situation when you are not able to make your wishes known. In normal times, American hospitals tend toward extreme efforts to prolong life at any cost. Not everyone wants that, or if they do, they should be clear about that too.

How can you assure that your care matches your personal values? The first and hardest step is to think through the issues. End of life care is emotionally hard to think about, and also intellectually complex if you really get into the details. Talking to your doctor is a good way to sort things out. There are three big categories to ask yourself about: would you want CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) to restart your heart if it stops; would you want to be put on a ventilator if you cannot breathe; and would you want artificial nutrition and hydration (such as a feeding tube) if you can’t eat.

The ventilator question is particularly relevant in the current situation. The outcomes for COVID-19 patients who require ventilation are not great. Early reports from New York (this paper) found staggering mortality rates for persons requiring mechanical ventilation (75-97%). Since then, much has been learned about critical care of COVID-19 patients, and equipment shortages haven’t been as much a problem in other parts of the country, so those COVID-19 mortality rates are clearly too high. This article quotes an expert estimate that ventilator mortality will be in the range of 25% up to maybe 50%.

What’s not included in raw survival rates following mechanical ventilation is the long recovery after. I already mentioned the article about coma and neurologic problems that strike some patients, but all patients face some period of extreme fragility as they get their strength back.

Would you choose to be ventilated for COVID-19? Put your answer in writing. A living will “is a written document that helps you tell doctors how you want to be treated if you are dying or permanently unconscious and cannot make your own decisions about emergency treatment.” A lawyer can help create a living will, but you do not have to use a lawyer. See the NIH article for more details.

Healthcare Proxy

Trying to understand and anticipate future medical decisions is really hard. But you don’t have to figure out everything. In addition to (or instead of) a living will, everyone should designate a trusted friend or family member to make medical decisions on your behalf when the time comes. This person is called a healthcare proxy and you give them durable power of attorney. This person should understand your values, and then in a particular situation they can apply your values to make a decision as they believe you would do for yourself. That way, any situation not adequately covered by a living will can be addressed by a living person on your behalf. Make sure this person is aware of your designation, and put it in writing in a format that will be legally recognized in your state.

Advance Directives and the Coronavirus Pandemic

It’s not fatalistic or pessimistic to recognize that we all are going to die someday. You don’t have to be desperately afraid of the coronavirus to prepare for that reality. Hubby and I are both healthy and middle aged, and we have living wills and healthcare proxies. If you do not, today is as good a day as any to create your plan.

A book I highly recommend about end of life issues:

Amy Rogers, MD, PhD, is a Harvard-educated scientist, novelist, journalist, and educator. Learn more about Amy’s science thriller novels, or download a free ebook on the scientific backstory of SARS-CoV-2 and emerging infections, at AmyRogers.com.

Sign up for my email list

Share this:

0 Comments