Beginning of the End

I’m a little choked up as I write this:

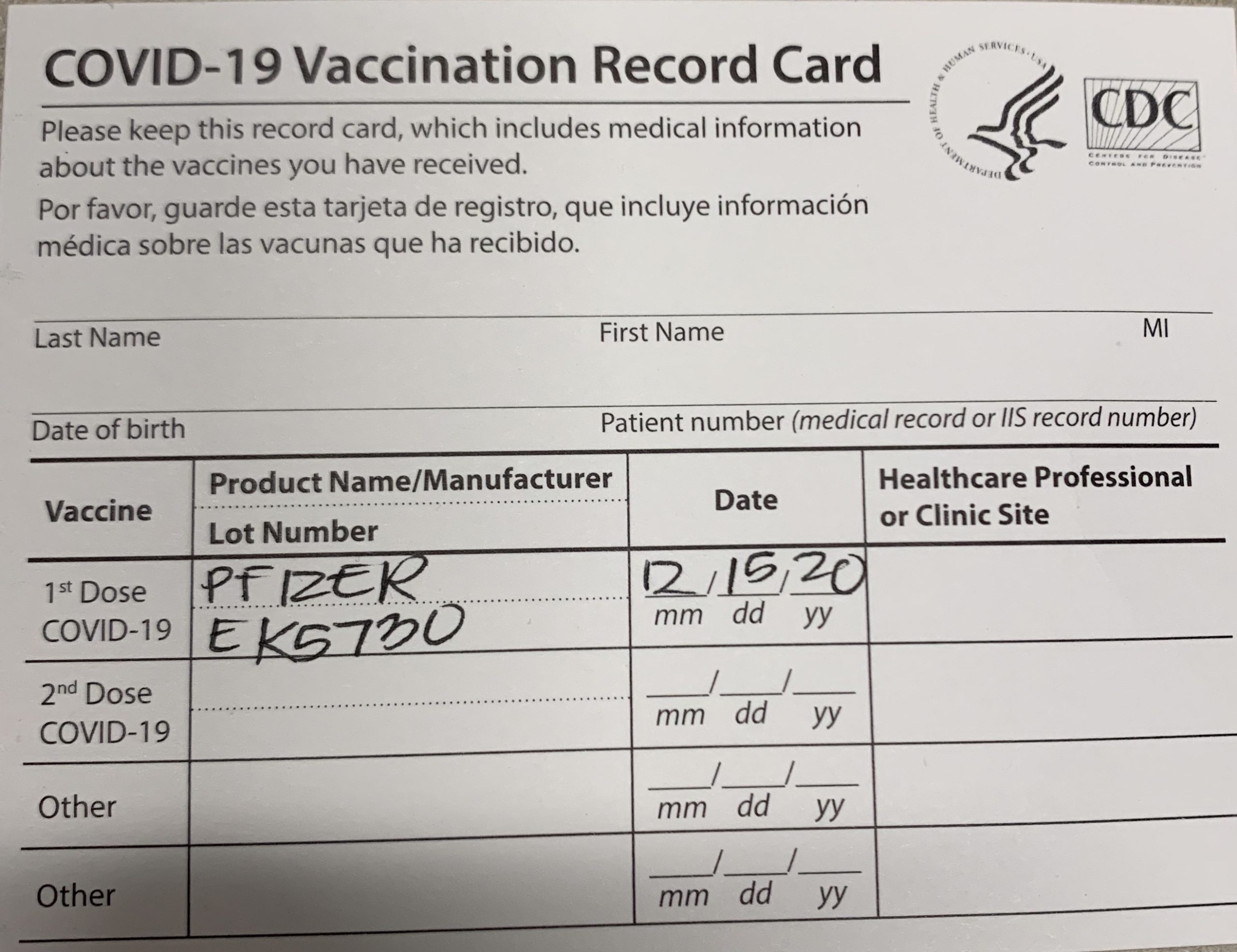

Hubby just got vaccinated.

Today at the university hospital where he works, he was injected in his left arm with the first dose of a two-shot series to protect him against COVID-19. His muscle cells will absorb a carefully chosen fragment of RNA from the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, wrapped in a fatty bubble. Enzymes in his cells will read the information in that RNA and use it to manufacture a tiny bit of one critical protein from the virus–the so-called “spike” protein. That protein will be presented to the cells of his immune system, and his immune system will react.

Maybe an alarm will sound in his body, and his immune system will lob a few defensive attacks: aching or swelling in his arm, perhaps a feeling of tiredness, maybe a bit of fever. Maybe his immune system will calmly accept the lesson without noticeable side effects. Either way, his body is about to get an education in how to recognize and resist this new viral villain. And if the coronavirus tries to invade his body in the future, his lymphocytes will be ready. We know who you are, they’ll say. And then they’ll destroy the virus.

I’m feeling pretty emotional about this moment. Sure, I’m grateful that hubby will have some protection when he starts a two-week shift in the cardiac care unit the day after Christmas, when COVID cases will probably be running rampant from a holiday boost. But that’s not why his text message made me teary. This vaccine is a tiny miracle in a syringe. Honestly, I did not believe it would happen before it was too late to make a difference.

That Pfizer/BioNTech and others have accomplished this is staggering to me. Pause for a moment to consider the magnitude and complexity of what has been done, and how deep are the foundations of this success.

Viruses have probably existed on earth for billions of years. Humans became consciously aware of their existence only around the year 1900; when the last great pandemic hit in 1918, we didn’t know what influenza virus was. The role of RNA in directing the production of proteins was worked out in the early 1960s. The first recombinant DNA molecule was created in 1972. The cost of sequencing a (human) genome was a hundred million dollars in 2001; by 2015, it was about a thousand. Similarly incredible advances in protein modeling, structural genomics, immunology, and virology in recent decades all came together in a perfect “storm” in 2020, making it possible to go from identifying an entirely new virus, to designing, testing, and manufacturing a safe and effective vaccine based on an entirely new technology in about nine months. On top of the science, consider the social organization required. Huge multinational companies like Pfizer, and smaller local startups like BioNTech and Moderna, sometimes working together. Big government programs like Warp Speed. Financing from investors and internal budgets and the public sector. Clinical trial design involving statisticians, clinicians, record keepers, hospitals, volunteers. Data collection, interpretation, and regulatory work inside Pfizer and at the FDA. Precision manufacturing technology to scale up production. Logistics to plan, pack, ship, track, preserve, distribute the vaccine ultracold.

I could go on. What I want to say is this. As a society, we’ve screwed up a lot of things in our pandemic response, but not all of them. Our collective failures and victories mirror who each of us is as a human being. We are flawed. We make terrible mistakes. We weigh difficult decisions with inadequate information, and make tradeoffs that hurt us and others. But we are more than our worst choices. We are also capable of greatness, and goodness.

You may choose to focus on what’s wrong with America. Today, I am in awe of what’s right.

Questions? Contact me.

Amy Rogers, MD, PhD, is a Harvard-educated scientist, novelist, journalist, and educator. Learn more about Amy’s science thriller novels, or download a free ebook on the scientific backstory of SARS-CoV-2 and emerging infections, at AmyRogers.com.