Should colleges reopen in the fall? A framework for thinking about coronavirus on campus

chensiyuan / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

This is an interruption in my Endgame series on how the pandemic ends, and how we get there. Endgame part 5 coming soon.

Yesterday a friend of mine who happens to be a college dean asked for “my take” on the difficult question of how to safely reopen college campuses in the fall. While trying not to claim expertise I do not have, I reflected on this question and replied with a framework for thinking about how this is as much a values question as a science one.

Dear xxx,

Your students and college are lucky to have you. I know how much you care about them.

What an impossible situation for you, and all the other university administrators of the world. Thank you for the honor of asking my opinion. As I’ve worked on my response, I see that you have inspired a blog post.

From an epidemiology point of view, I am not the level of expert you need for solid advice. However I am constantly thinking about these things from a slightly “higher” perspective, so I will share with you a framework that might be helpful.

As you describe from some of your proposed models for seating, classes, and dorms, there are lots of NPIs (nonpharmaceutical interventions) that can be used to decrease the likelihood of spreading coronavirus on your campus. Choosing among them, unfortunately, is probably a shot in the dark. I doubt there is much good data to let you evaluate their relative effectiveness in advance. That means your community values will be a big part of the decision.

If I were trying to decide what my college is going to do, I would begin by being very clear about what matters most, and by getting a sense of what my faculty, staff, and students are willing to accept. Because obviously there are competing interests here.

A phrase I see a lot in education these days is “Your children’s safety is our highest priority.” It’s a bland assessment that everyone seems to accept, and expect. But is it true? Should it be true? Taken to a logical extreme, if “safety” is the only thing that matters, we would never let our children leave the house. In fact, getting a good education, having social experiences, and living a life are excellent reasons to face the dangers of the real world.

This tradeoff is massively heightened, of course, by the existence of coronavirus. But I think the principle holds true: safety is one value among many.

So to begin, you (plural) need to honestly ask yourselves:

Is the safety of our students and staff the only, or by far the most important, consideration?

If so, I think you need to go online only. Everything that makes a college experience what it is involves person-to-person contact, and groups. It’ll be hard to keep coronavirus out of your community even with the most creative NPIs.

Should you delay the start of classes?

A gamble. What do you think is going to change between August and say, November?

What will NOT change is vaccination status. Your students will not be vaccinated in 2020. Even if a miracle occurs and a vaccine is available and being distributed this fall, healthy college-age people will be at the bottom of the priority list and will get it last.

Again unless a miracle occurs, the virus will still be circulating at some level in the community. That level could be much lower than it is now, but there are no guarantees. It could also be higher.

Health care for COVID patients might have improved, treatments better, survival greater.

I think the likeliest change between now and November isn’t biology or medicine; it’s social. Our attitudes toward anything coronavirus-related are evolving quickly. I can’t imagine what our November selves will be thinking about risk.

Which brings the next question for you:

Besides safety, what else do we value that is also important, and worth taking a risk for?

This list might include the financial survival of the entire university, certainly a thing of great importance on many levels. Also on the list: providing students with the kind of education they want and deserve, and the many other services that the school provides to foster the mental health and well-being of students.

If these other goals matter enough, then you should plan to open campus in the fall. You would need to be absolutely clear with each other that there is no model for “safely” opening, at least not in the sense that most Americans seem to understand “safe.” It would not be risk-free. It’s likely that a coronavirus case, or a cluster of cases, would be associated with the university. Are your stakeholders prepared for that? Or would this send everyone into a panic, and require closure and sending the students home again? If you re-open, don’t sugar-coat it or you’re setting yourself up for failure and liability.

For this to work, your students will have to buy-in. How risk-averse are they? How badly do they want to return to campus? A quick survey of college parents I know reveals that quite a few are eager for their kids to return to school even with coronavirus risk. Of course some are not. I wonder if there is anything the colleges could do to convince them. Maybe not, as NPIs only go so far. Students will make their own choices about returning to campus if given the option. They will also make their own choices about whether to enroll if instruction is online only.

If the decision is made to re-open, then the conversation is about details of NPIs. I have nothing to suggest on that. But I will point out another strategy of harm mitigation. NPIs focus on reducing transmission of the virus in your community, and that’s important. But another way to reduce harm is to consider who is on campus.

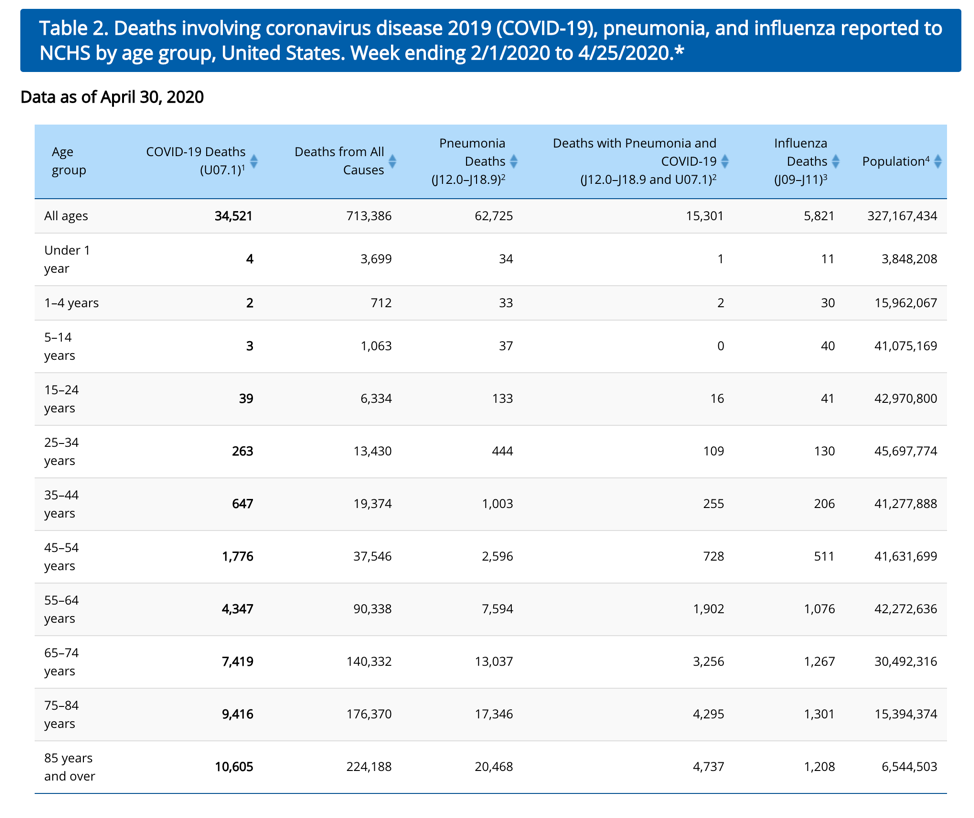

Young people with no pre-existing medical conditions are at exceedingly low risk of dying from COVID-19. I’ve attached two sets of data to support this assertion, but obviously your college would want to consult with an expert on this point. In the CDC statistics (which are compiled in a particular way, so their numbers are different from other sources), 48 people under the age of 25 have died of COVID in the US, out of 34,521 total American deaths. That is about one-tenth of one percent of the total COVID deaths.

Source: US Centers for Disease Control https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/index.htm

One could make the argument that suicide as a consequence of school closure (and all the attendant disruptions) is a greater health risk to this age group than coronavirus. (THIS IS STATISTICAL SPECULATION, I don’t have any numbers on suicide or the quantitative impact of school closures on suicide rates.)

The New York City data are broken down differently. They group ages 18-44, a range that captures a lot more deaths. (By the CDC data, age 15-44 cohort had twenty times more deaths than age 0-24.) In NY data, ages 18-44 accounted for 507 deaths out of 12,571 total. NY offers something else: a breakdown based on pre-existing conditions. In the 18-44 age group, at least 80% of the COVID deaths occurred in people with an underlying medical condition.

Taken together, these data suggest to me the following strategies for re-opening a college:

- Invite students back to campus at the usual time but encourage those with an underlying medical condition to take the term off (or offer them a plan for remote instruction)

- Make a reasonable, but not excessively disruptive, attempt at NPIs on campus to minimize local transmission.

- There may be local rules you must comply with, such as limiting the size of “gatherings” in lecture classes

- Focus NPI effort on protecting your faculty and staff, who are probably at much higher risk than your students

- Have a plan for how you will respond to a campus outbreak. If that plan is to close everything, then don’t bother opening in the first place.

Other issues to consider:

While your students may be at low risk because of their age, they can still be carriers of the infection into the community, or their homes if they commute. In this sense, I think fully residential colleges are at an advantage despite the crowding inside dorms. Mitigating this risk is a separate policy issue for your school. It would probably emphasize responsible social distancing by students when they leave campus. For residential colleges, it might include travel bans: nobody goes home for Thanksgiving.

The best-laid plans of mice and men… If COVID is raging out of control in the community in August, and local hospitals are overwhelmed, you’ll have no choice but to stay remote / online so that you don’t add to the problem.

I predict that the choices universities make about re-opening will reflect the culture and values of the administration, more than they reflect technical issues with NPIs. Some schools will be highly risk-averse; they will not accept the possibility of a newspaper headline about coronavirus on their campus, or that a student could die of coronavirus while enrolled. Others will accept these risks as a reasonable trade-off for the benefits of bringing students back to campus, and because their students, families, and communities support this choice.

Good luck.

Your friend,

Amy

Amy Rogers, MD, PhD, is a Harvard-educated scientist, novelist, journalist, and educator. Learn more about Amy’s science thriller novels, or download a free ebook on the scientific backstory of SARS-CoV-2 and emerging infections, at AmyRogers.com.

Sign up for my email list

0 Comments

Share this:

0 Comments