Coronavirus testing: how it works, and its limitations

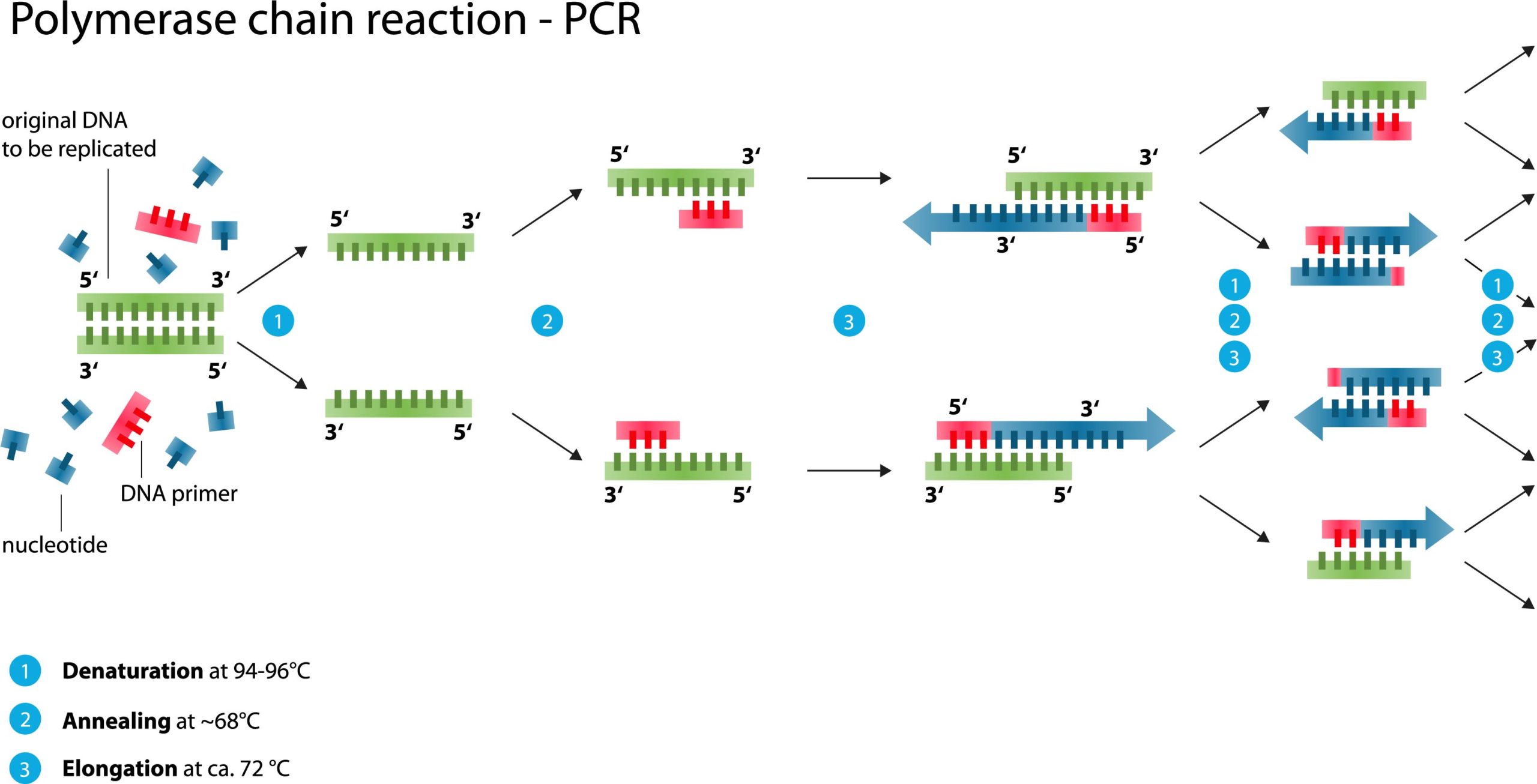

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Coronavirus tests (part 1): Detecting viral RNA

Coronavirus testing has been top of the news for weeks. As more and faster “coronavirus tests” roll out across America, another type of laboratory test related to coronavirus is entering the conversation. In this series of posts, I’ll explain what these two types of tests are, how they are performed, their limitations, and how they can be used.

When people say “coronavirus test”, they generally are talking about a diagnostic test to detect the presence or absence of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus) in a person. The purpose of this test is to give a simple yes or no answer to the question, am I infected? Is the virus present in my body?

The other test is for antibodies against the coronavirus. The purpose of this test is to answer the question, was I recently infected by SARS-CoV-2, whether I was aware of the infection or not?

The first test identifies people who are potentially infectious. The second test identifies people who are potentially immune. Both tests will be needed for our society to resume normal activities in a safe manner.

The basic coronavirus test is a miracle of modern medical technology, developed within an astonishingly brief period of time after SARS-CoV-2 was first discovered in December. It is not a single test but many similar tests independently developed by different countries, private testing labs, pharmaceutical companies, public labs, universities, etc. I think it’s important to understand that these tests have a range of accuracy and none are perfect. Given the urgent circumstances under which the tests have been developed, they have been rushed through regulatory approval, or exempted from approval under FDA Emergency Use Authorization. The tests are not 100% reliable; no medical test is. So if you’re anxious because you want a test but can’t get one, keep in mind that a coronavirus test result might not matter because it could very well be wrong. If you have a fever and cough, you should behave as if you have COVID-19 regardless of whether a test comes back negative or positive. A test result should never override common sense. As an old medical dictum says, treat the patient, not the test.

The CDC’s coronavirus test and nearly all others use the same underlying technology, called RT-PCR (reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction) to detect viral RNA. RNA is an information-carrying molecule, similar to DNA. RNA and DNA both encode information in a sequence of four chemical building blocks, much like a language written using an alphabet with four letters. Humans store their permanent genetic library in DNA. Coronaviruses, on the other hand, use RNA. The test looks for two or three RNA sequences that are unique to SARS-CoV-2 and not found in any other coronaviruses.

RNA is less stable and harder to work with than DNA. So the first step in the coronavirus test is to convert any viral RNA in the sample into a DNA mirror image. This is called reverse transcription. In the subsequent steps, molecular probes search for the viral sequence(s) of interest. In order to detect even the tiniest amount of virus in a sample, the test then amplifies or copies the viral sequence over and over until enough material is present to detect. This amplification series is called polymerase chain reaction or PCR.

As I said, like all medical tests, coronavirus tests give the correct answer most of the time, but not all of the time. Some people who test negative are actually infected with the virus. Some people who test positive actually are not. I’ve read many anecdotal tales of people with COVID-19 symptoms whose test came back negative, but days later as their disease worsened a re-test came back positive. One limitation of the coronavirus test is not the fault of the RT-PCR, but rather the sample we give it. Because COVID-19 is primarily an infection of the respiratory system, testing is done by swabbing organic material from a person’s nasal passages. But SARS-CoV-2 can also cause gastrointestinal sickness (diarrhea, vomiting). What if a person is carrying the virus in their gut but not in their nose? Their coronavirus swab will come back negative. Any particular swab could, at random, miss the virus.

A positive test means coronavirus RNA was present in the specimen. But how do we interpret that result? We don’t know whether that means the person is necessarily infectious. It is safest to assume that they are. We know that you can give the virus to others without having symptoms yourself. At this time we don’t know how long an asymptomatic person can do that, or how long they will continue to shed virus after recovering from COVID-19. I have seen a report of a person still testing positive thirty days after recovery but most patients seem to clear the virus sooner once their symptoms are gone. The test cannot answer these epidemiologic questions. The test cannot tell us what its answer means or what we should do with the information for a particular person.

I’ve raised these complications to emphasize that while coronavirus testing can generate extremely important information about the progression of the pandemic in a community, on an individual basis, a single test result is not the only, or even the most important, determinant of what actions you should take.

In my next post, I’ll discuss the antibody test.

Amy Rogers, MD, PhD, is a scientist, novelist, journalist, and educator. Learn more about Amy’s science thriller novels, or download a free ebook on the scientific backstory of SARS-CoV-2 and emerging infections, at AmyRogers.com.

Do you like my science journalism? Read Science in the Neighborhood and learn, where does my tap water come from? How are mosquitoes managed? What happens after I flush? Where does my electricity come from?

Do you like my science journalism? Read Science in the Neighborhood and learn, where does my tap water come from? How are mosquitoes managed? What happens after I flush? Where does my electricity come from?

0 Comments

Share this:

0 Comments