Coronavirus incubation period: by then it’s too late

They say that the best time to plant a tree is ten years ago. The second best time is today. We’re looking at a similar situation with the SARS-CoV-2 (coronavirus) pandemic.

Infectious disease outbreaks have a momentum and timeline that separates cause and effect by a period of time. The things we did in the past bear fruit today, whether that was buying ventilators for the Strategic National Stockpile two years ago; expediting the production of coronavirus diagnostic kits two months ago; or cancelling a conference/convention two days ago. A decision is made, an action is taken (or not), and for a while we don’t experience the consequences.

This is a problem when outcomes are uncertain, and the best decisions are costly or painful. Nobody wants to experience discomfort today for the promise of relief against a future harm that might not happen. It’s as true for pandemics as it is for earthquakes and hurricanes. Why should I evacuate my low-lying coastal home when the storm might not even make landfall? By the time the storm hits, it’s too late. Same with the spread of COVID-19: once your local hospital ICU is overflowing, you can’t go back and try harder at containment.

Another problem is every disease-causing virus has an incubation period. This is the time between exposure/infection and having symptoms of the disease. This means altering the course of an epidemic is like turning an oil tanker: you won’t see an immediate change from your effort.

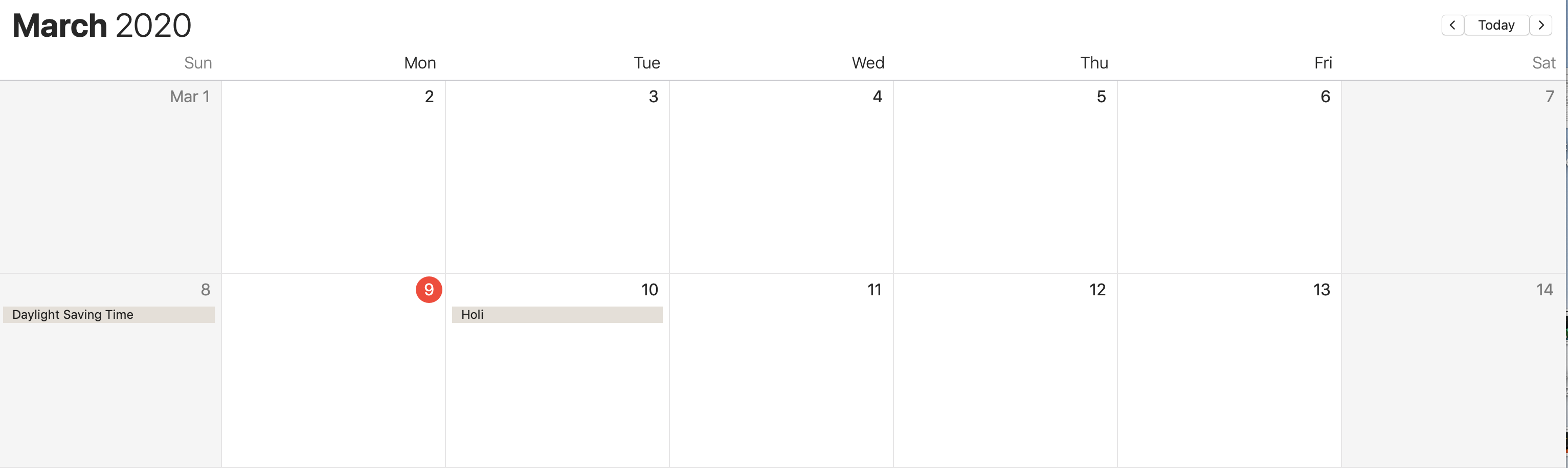

Best current estimate of the incubation period for SARS-CoV-2 is 2-14 days. That means if you quarantine every person and totally stop all transmission of the virus, you’ll still see an increase in the number of cases for about two more weeks.

What if a community has a handful of COVID-19 cases–not too many, and the hospitals have plenty of room. Should the community go into lockdown to prevent that handful of cases becoming a bushel?

Let’s say they do. Two weeks later, they still have just a handful of cases around town. So was the lockdown hype? Overreaction? There is no way to tell, because we can’t turn back time and run the experiment again without the intervention.

Let’s say they don’t go into lockdown. Two weeks later, the trickle of cases into the local hospital has become a flood. Strong action is clearly needed. The city goes on lockdown to arrest the spread of the virus. But here’s the rub: no matter how strong the action they take, the number of cases will continue to rise for another 2-14 days because of the incubation period of the virus. By waiting for the situation to get bad, they guarantee that it will get considerably worse before it gets better.

I have tremendous sympathy for anyone in a decision-making role right now. As these two scenarios illustrate, in public opinion you’re damned if you do and you’re damned if you don’t. Decisive, effective action early can create obvious pain with less-than-obvious benefit (things stay normal). Choosing to delay action still creates the pain of the action, and then the action can look ineffective because of the lag.

Get the scientific backstory on SARS-CoV-2 and emerging infections. Read my concise ebook “The Coming Pandemic” for free. If you like it, please share with others and leave a review on amazon.

0 Comments

Share this:

0 Comments