Public health effort reveals how “structural racism” can impact COVID mortality.

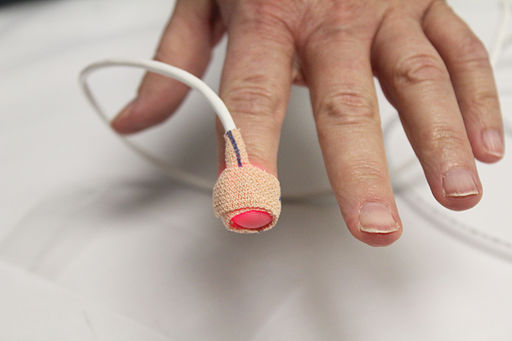

A pulse oximeter (pulse ox) device measures the oxygen saturation of blood. Public domain image courtesy of Wikimedia.

“Structural racism” is vague. An article showed me how it actually can impact COVID mortality.

People of color in the US have in general been hit harder by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic than white Americans. Some of the specific explanations I’ve heard include: more essential workers and people who can’t work jobs from home; denser, multigenerational housing arrangements; higher rates of preexisting conditions. But I’ve also heard the vague assertion that “structural racism” is to blame. While that statement may be accurate, to me as a scientist it feels like a cop-out. What specifically does “structural racism” mean in the context of COVID-19? What measurable or actionable aspects of public health constitute this nebulous idea?

Today I read an excellent story that was not intended to answer my questions, but by showing the reality on the ground at Fort Apache reservation in eastern Arizona, the article illustrated in a concrete way how underprivileged communities experience the pandemic differently.

As a bonus, the article is a positive story about effective public health techniques that are saving lives and have reduced the death toll from COVID in this vulnerable group. (The article also happens to be written by one of my favorite science journalists, Gina Kolata. Click to read some of her other work, or get her fabulous book on the 1918 influenza, Flu.)

If you can’t access the NYT piece, it’s based on a report just published in the New England Journal of Medicine here.

In summary:

A regional hospital in rural eastern Arizona that serves about 18,000 Native Americans launched a well-run, labor-intensive contact tracing program to try to mitigate the coronavirus infections raging through the community (at about ten times the rate of Arizona as a whole). The effort relies on in-person home visits and repeated followup.

The intent of most contact tracing is to identify people who may have been exposed to the virus, and get them to quarantine, etc. in order to minimize the number of new infections. In the case of these crowded households with few resources, in-home isolation is virtually impossible. So the public health focus shifted to monitoring the COVID-positive patient and other family members for signs of illness.

The key to their success: a pulse oximeter device, which quickly and easily measures oxygen saturation of the blood.

One of the peculiar features of COVID-19 lung disease is “happy hypoxemia.” As with other pneumonias, patients have abnormally low amounts of oxygen in their blood. Unlike other pneumonias, COVID drops oxygen levels much lower without making the patient short of breath. An oxygen saturation level that for another disease would leave the patient desperate for air, seems to be tolerated with minimal symptoms in COVID patients. (This bizarre tolerance for low oxygen in COVID patients is the reason why ventilators were used heavily at the start of the pandemic, but doctors learned that putting a patient on a ventilator based only on oxygen saturation caused more harm than good.)

COVID patients, in other words, often don’t realize how sick they are.

The public health teams visiting homes on the reservation used their personal knowledge of the families, and simple tests–walking around a room, a pulse ox reading–to identify who needed to go to the hospital. They were able to get people into care sooner, often before the patient or family would have considered seeking it. In theory, getting these COVID patients on oxygen before their lungs were severely damaged may have saved lives.

Why did this story strike me as a tale of “structural racism”? Because in these simple anecdotes, I could see how the cumulative, systemic effect of deprivation on the reservation led to a specific moment and decision in a family’s life–when grandpa got sick, and they took him to the hospital too late. The article doesn’t get into why this would be the case, but we can all imagine the factors. The geographic isolation of the reservation, miles and miles from a hospital. Maybe an unreliable car, or no car available, or no money for gas. Maybe no internet or news, so a lack of understanding of the disease. Maybe a lack of health insurance, or lack of experience navigating the health care system. Maybe a lifelong habit of fending for oneself, or of mistrusting doctors. Or any number of subtle psychological factors that could tip the balance between saying, “Let’s get you to the hospital” and putting it off until tomorrow or the next day. These factors are not race-based in themselves, of course, and are not unique to communities of color. But their prevalence in a Native American reservation is rooted in a hundred-plus years of history that was definitely formed by racism.

Amy Rogers, MD, PhD, is a Harvard-educated scientist, novelist, journalist, and educator. Learn more about Amy’s science thriller novels, or download a free ebook on the scientific backstory of SARS-CoV-2 and emerging infections, at AmyRogers.com.

Sign up for my email list

Share this:

0 Comments