The Coronavirus Endgame 3: Herd immunity is not an evil plot

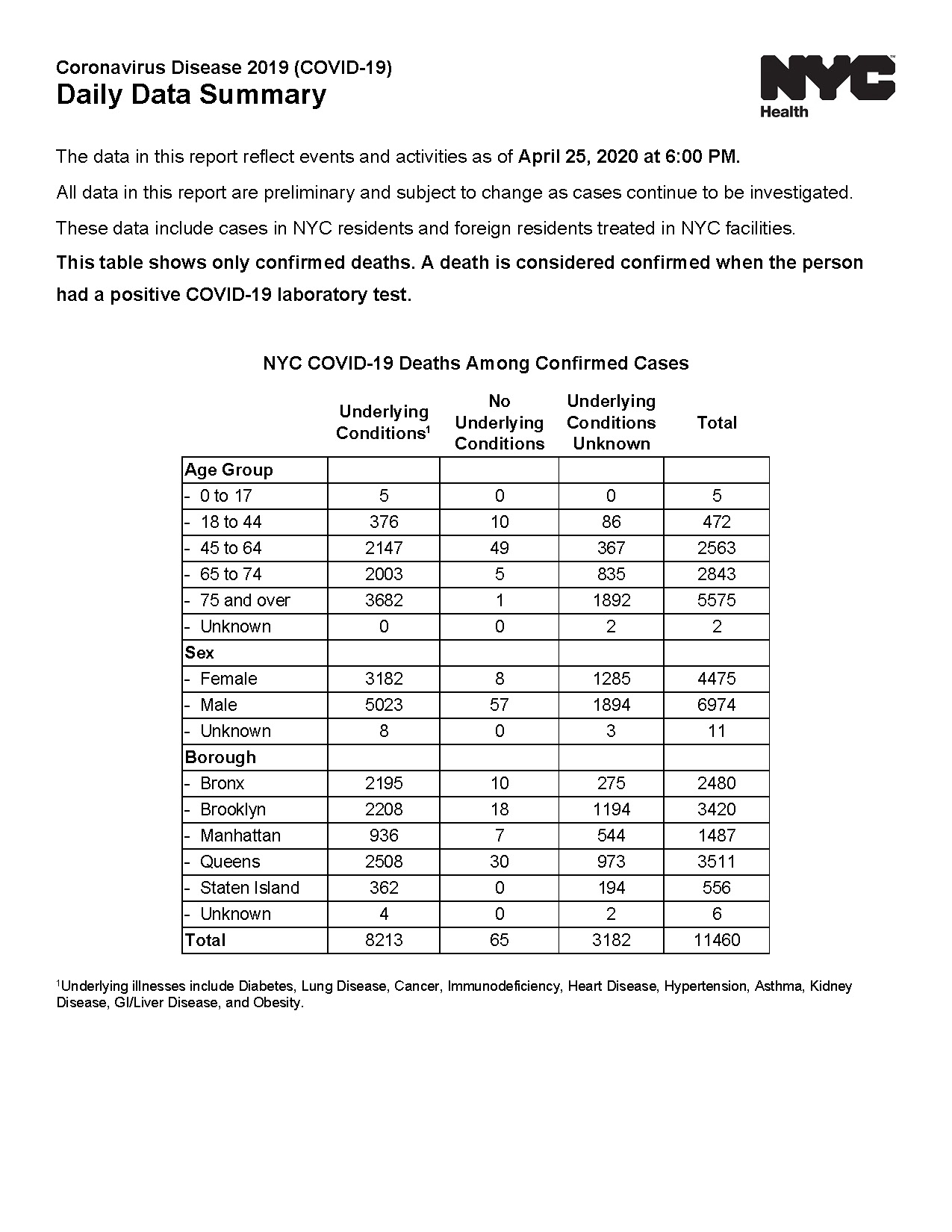

Total deaths, daily summary, April 26. New York Health https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data-archive.page

Part 3 of a series on how the pandemic ends, and how we get there. Please share. Link to part 1 and part 2.

It’s time to not freak out about herd immunity

As I discussed in my coronavirus endgame post #2, our current national strategy is to use nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPI, which includes “social distancing”) to drastically reduce virus transmission. This effort has successfully flattened the curve. Virtually all US hospitals are operating within capacity at this time, and most have resumed some of the non-emergent services that were halted in March.

Does this success bring us any closer to the end of the pandemic? Not really.

In coronavirus endgame post #1, I explained the most likely way the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic will end. The virus will persist, and people will continue to die of COVID-19 at some frequency. This is the pattern for nearly all the viruses you know: influenza, HIV, measles, hepatitis A, etc. An equilibrium is reached over time because of NPIs and behavior changes (such as hand washing for hep A and condom use for HIV), medical therapies, vaccines, and herd immunity.

The same will be true for the new coronavirus. Our strategy should reflect efforts in each of these categories, because they all matter in the long run.

We’re explicitly putting effort into the first three. It’s time to talk about the fourth: herd immunity.

In our early, panicky national conversations about how to cope with the pandemic, herd immunity got off on the wrong foot. In a notorious press conference on March 12, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson left his constituents with the impression that their government was throwing them to the Darwinist dogs, that the national strategy was to achieve herd immunity by letting the virus run its course, and hundreds of thousands of Britons would die preventable deaths in order to save the economy. None of this was quite true, of course; this article has an excellent perspective on the decision-making process, how the messaging got muddled, and why Johnson changed plans a few days later.

Regardless, “herd immunity” became a third-rail topic, not to be touched.

But guess what? Nature doesn’t care whether you think “herd immunity” sounds evil. One way or another, it’s coming to a planet near you.

Call it population-level immunity or community immunity if that makes you feel better.

Herd immunity as a strategy is implicit in our effort to develop a vaccine against the coronavirus. No vaccine confers protective immunity in 100% of the people who get it. And many people are medically unable to be vaccinated at all. Therefore any vaccination campaign to protect a population against a virus relies on immunizing enough people to create herd immunity to protect the rest. For SARS-CoV-2, Johns Hopkins public health experts estimate at least 70% of the population must be immune. Higher is better, but it doesn’t need to be 100%.

70% translates into almost 230 million Americans if the vaccine is extremely effective at provoking a protective immune response in everyone. Most likely, it will not be, in which case a higher percentage of the population would have to be inoculated to get 70% protection. On top of that, many vaccines don’t “work” on the first dose. A second or even third booster is needed. Now we’re talking about manufacturing and administering close to a billion doses of a vaccine that doesn’t yet exist, just to protect the United States.

The challenge of reaching herd immunity solely by vaccination can’t be overstated. (I’ll delve into more details in a future post.) We need to make progress toward herd immunity by way of natural infection to complement a future vaccine, and we need to make this an explicit strategy. In terms of my previous post, this is Strategy C.

In late February when the threatmeter drifted into the red in the US, I would not have advocated for this strategy the way I do now. The reason? Data. We’ve learned a lot in the last eight weeks.

New data, new strategies

What have we learned about SARS-CoV-2 (the virus) and COVID-19 (the disease) that shifts the risk-benefit calculation in favor of a Strategy C (controlled movement toward natural immunity)?

- The overall mortality rate of the virus is lower than the worst-case predictions that were made initially; and more important,

- We can identify categories of people who are at significantly lower risk than others

Let’s start with my first claim. The single most important piece of information about the virus remains uncertain: out of all the people who are infected by SARS-CoV-2, how many will die? This mortality rate determines our societal response. How far we’re willing to go to protect ourselves, how much we’re willing to sacrifice, depends entirely on how many lives are at risk. If this new virus killed half of all the people infected, I guarantee we would not see street protests advocating for a return to normal economic activity at this time; people would be scared witless. In reality, SARS-CoV-2 kills a much smaller fraction of those it infects. Smaller enough that reasonable people can disagree about how much it’s worth to resist.

This much seems clear: the upper limit of mortality is less than 5% overall, probably a lot less. The main reason we’re not sure is because the virus does not cause symptoms in everyone who catches it. Many people have been infected but not counted in the total number of cases. This makes the mortality rate (deaths divided by total number of cases) artificially high.

I don’t want to get into the weeds about best estimate of the overall mortality rate. An exact number is not important for my argument, because I’m not as much interested in the overall mortality as the mortality within certain groups of people.

Which is my second claim, that we can allow people who are low risk to build up the firewall of herd immunity with minimal loss of life.

Who are these people? Healthy Americans under the age of 45, including children.

I’m not an epidemiologist working on the front line, so I’m not the person to drill down the details. But one persuasive piece of evidence is in the image at top. (Link to pdf version) The New York City Health Department releases daily reports of COVID deaths among laboratory-confirmed cases. In this particular report format (you can find others here), the deaths are broken down by age, sex, and whether the victim had any underlying medical conditions. These are defined to include “Diabetes, Lung Disease, Cancer, Immunodeficiency, Heart Disease, Hypertension, Asthma, Kidney Disease, GI/Liver Disease, and Obesity.”

The most striking result: Healthy people under the age of 45 account for 10 deaths out of 11,460 total. Yes, ten. (86 people in this age range perished with “underlying conditions unknown” so ten might be a little low. But even if every one of those unknowns were totally healthy—which is unlikely—then the number only rises to <100 out of 11,460 fatalities.)

The next age cohort, 45 to 64, continues this general pattern of a preponderance of deaths occurring in people with preexisting conditions. More people in this age group have such conditions, so the number of deaths is higher overall, but maybe a proper statistical analysis would say healthy people in this age group could also be part of the herd immunity strategy.

People are going to die

I’m not the only person who has come up with a Strategy C. The British made a plan for it, the Swedes are living it, and the Israelis are considering an extreme version of it. I’ll get into the details in my next post. Strategy C boils down to this. We loosen social distancing for people at low personal risk of dying from COVID-19, while protecting people who are waiting for a vaccine because catching the virus would be too risky for them. Yes, some people at “low risk” will die. But not many, and there is no path forward, or strategy, that doesn’t involve people dying.

Obviously the details matter a lot, and the strategy carries certain risks. The main point I want to end with today is to advocate for a perspective shift. In the past two months, we’ve fought to stop transmission of the coronavirus, buying time to learn, to prepare, and to work toward a vaccine. In the next phase, we may need to welcome limited transmission in order to build up herd immunity among low-risk groups, and to move us closer to the endgame.

Coronavirus Endgame PART 4: A plan to relax social distancing {coming soon}

Amy Rogers, MD, PhD, is a Harvard-educated scientist, novelist, journalist, and educator. Learn more about Amy’s science thriller novels, or download a free ebook on the scientific backstory of SARS-CoV-2 and emerging infections, at AmyRogers.com.

Sign up for my email list

0 Comments

Share this:

0 Comments