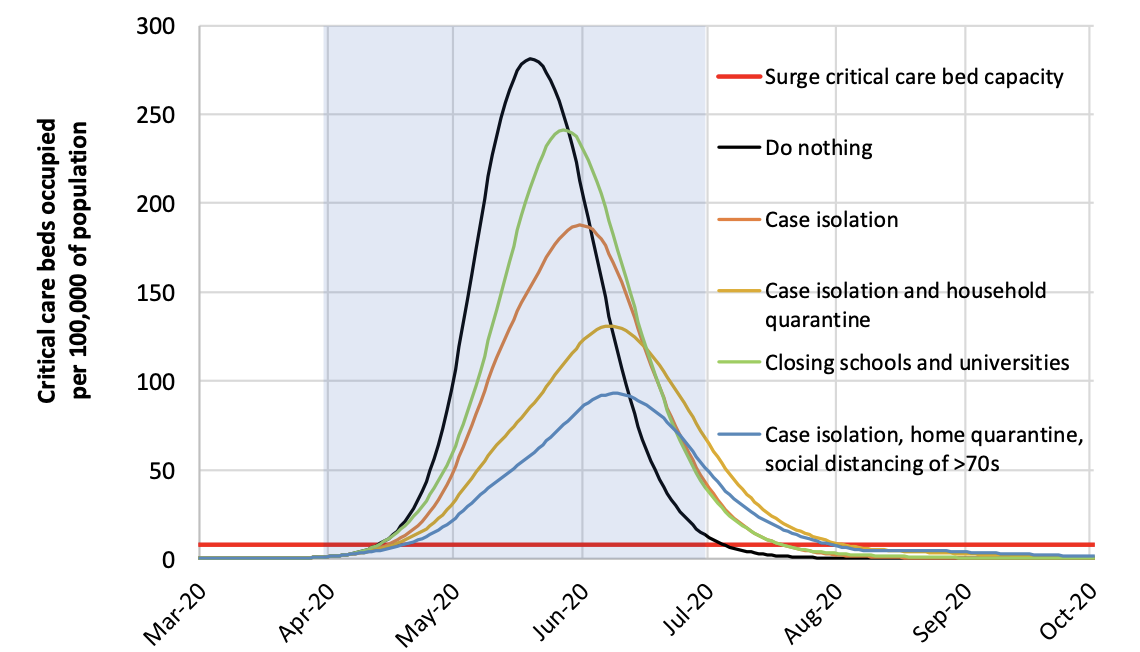

Coronavirus suppression, mitigation, and flattening the curve

Source: Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team

Coronavirus suppression, mitigation, and flattening the curve

Just eleven days ago, I blogged about whether the nascent social distancing movement was an overreaction. On that day (March 12), the WHO reported a global total of 44,279 confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and 6915 deaths. Today (March 23) those numbers are 332,930 and 14,510. Since then New York has become an epicenter of the pandemic, with more than 20,000 confirmed cases—over 5% of the worldwide total. About 15% of cases have required hospitalization. Almost 1 in 1000 metropolitan New Yorkers have the virus, showing that the virus has been circulating in the region for weeks. It’s very likely that New York City hospitals will soon be making decisions about who will, and who will not, receive intensive care, as is already happening in Italy.

I think most of us can now agree that the new coronavirus is real, and it’s a very serious problem. In that blog post of eleven days ago, I asked the question, how many deaths averted would it take to justify social distancing. While the number is ultimately unknowable, an influential study released by a London-based epidemiology group (Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team) predicted the US would see over 2 million COVID-19 deaths this year if no action was taken.

At present, the US has chosen to take actions to decrease those deaths. Our chosen weapon is distancing / shelter at home / physical isolation. (I’ll mention but not discuss further today, that distancing EVERYONE is not the only possible strategy. South Korea chose an approach that was more focused, using mass testing, detailed tracking and public posting of people’s movements, and quarantine of all contacts. At the present moment, that strategy is not an option in the US.)

Depending on how extremely you practice physical isolation, you get different impacts on the epidemic. It is possible to completely stop the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic and purge it from a population. The recipe is simple: you lock up every single human being for two weeks. After that time, everyone who was infected will either be sick or in recovery. You keep the sick isolated until they either recover or die. Everybody else goes about their business and there are no more deaths unless the virus is re-introduced from outside.

Given that we can’t do that in even a mid-sized city, we could try for suppression instead. Using somewhat less extreme measures, you can reverse the growth of an epidemic and reduce the number of cases. With suppression, fewer people actually get sick. China did this in Wuhan.

The next level is mitigation. Mitigation means to slow the spread of the epidemic, spacing out the number of cases over time. This is the “flattening the curve” thing you’ve heard about. The total number of people who get sick over time might or might not be reduced. Why is this helpful? Because if everybody gets coronavirus at once, the health care system is overwhelmed. When there aren’t enough respirators or hospital beds, people die of COVID-19 even though their lives could have been saved with adequate care. Non-coronavirus patients who need hospital services also are impacted. Flattening the curve saves lives even if it doesn’t reduce the total number of COVID-19 cases.

Unfortunately, flattening the curve doesn’t just lower the peak; it stretches it out, too. Successful mitigation means the virus continues to circulate in the community for a longer time than if we did nothing. It’s the difference between an explosion, and a slow simmer.

How long? In future posts, I’ll discuss what happened in Wuhan, and the coronavirus end game.

Learn more about Amy Rogers and her books, including a free ebook on the scientific backstory of SARS-CoV-2 and emerging infections, at AmyRogers.com.

0 Comments

Share this:

0 Comments