A Tale of Two Pandemics: The end of coronavirus (part 1)

Source: FiveThirtyEight https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/republicans-and-democrats-see-covid-19-very-differently-is-that-making-people-sick/

A Tale of Two Pandemics

My (elderly) parents just bought airplane tickets to spend Christmas with my sister, and they invited my family to come too.

There it is. The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in the US will be over at the holidays.

Okay, so I’m being snarky. But there’s something at work here.

In early May one of my favorite science writers, Gina Kolata, published this article entitled “How Pandemics End.” At the time I was myself imagining and writing about the future history of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, and how it might ultimately resolve. Kolata raises a fundamental point. In any infectious disease outbreak, there are two pandemics: a pandemic of actual disease, and a pandemic of fear.

These two pandemics have very different effects. The plague itself has direct medical and social impacts. The fear of the plague causes people to change their behavior in ways that also have social and medical impacts, but different ones. These “two pandemics” influence each other but are only loosely correlated, and they follow independent trajectories. One can be more severe in its effects than the other, and they may not peak or end at the same time.

In the old days before mass communication, the two pandemics probably tracked more closely to each other. You were afraid if you actually knew people who got sick, and you saw people dying with your own eyes. As I wrote previously, the degree to which we fear an infectious disease depends partly on how graphic or painful the symptoms are, how suddenly it strikes, who is worst affected and how many such people are stricken. The actual death rate has less influence on fear than you might think. Just because a disease is deadly doesn’t make it terrifying. Seasonal influenza is dismissed by many Americans as “just the flu,” not even worth the trouble of getting vaccinated.

Also consider tuberculosis, one of the great infectious disease killers of mankind. In the early 1900s, it’s estimated that 450 Americans died of TB every day and there are still more than 10,000 cases (not deaths) per year in the US. And yet, in Victorian England, “consumption,” as tuberculosis was called, was romanticized as a beautiful death.

“We see elements in fashion that either highlight symptoms of the disease or physically emulate the illness,” Day says. The height of this so-called consumptive chic came in the mid-1800s, when fashionable pointed corsets showed off low, waifish waists and voluminous skirts further emphasized women’s narrow middles. Middle- and upper-class women also attempted to emulate the consumptive appearance by using makeup to lighten their skin, redden their lips and color their cheeks pink.”

You sure didn’t see fashion trends inspired by smallpox, which covers people’s skin in fragile pustules that break away in bloody sheets.

In the modern era fear can spread far beyond a hot zone. People thousands of miles away can see the victims, track the statistics, and learn about what might happen to themselves. Remember the West African Ebola outbreak of 2014? Americans absolutely freaked out. We had an epidemic of fear with no epidemic of disease: a final total of eleven cases in the US.

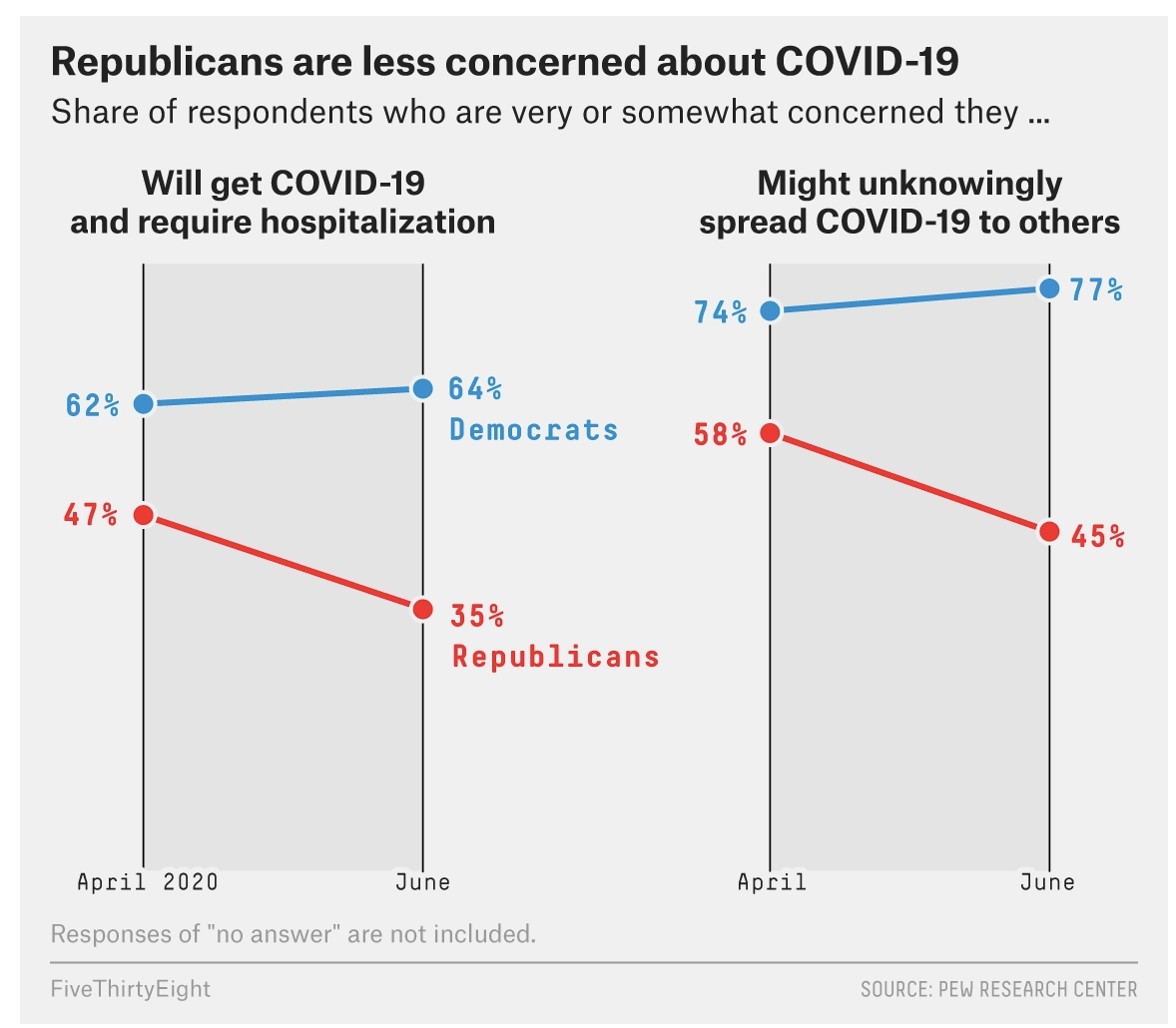

So as with any infectious disease, societal fear of COVID is not directly connected to the coronavirus’s health impact. In the US, COVID fear has split powerfully along tribal lines (see figure at the top of this post). Whatever the virus is actually doing has a relatively modest effect on Americans’ degree of concern about it. Sadly too, I sense that the hardening of tribal opinions means that many Americans are not open to adjusting their level of concern as the pandemic evolves.

Two roads diverged…

In my February ebook “The Coming Pandemic” one of the many accurate predictions I made about the coronavirus was this:

“Efforts to break the chain of transmission are likely to cause hardship for many more people than the virus itself.”

Despite over six million diagnosed cases and over 185,000 deaths in the US so far, the fact remains that for most of us, the most significant social and economic impacts of the pandemic have resulted from our collective response to the virus more than the disease itself. The pandemic of fear/caution has been our primary personal affliction.

That’s a good thing. It means most of us have been personally spared by COVID but we’re making sacrifices for the welfare of others. The strong but painful actions taken in March and April were prudent. They were also successful in flattening the curve, buying time for vaccine development, learning and implementing a huge spectrum of non-pharmaceutical interventions (social distancing), and studying the biology of the virus.

But our personal experiences are frequently—and appropriately—reducing our fear. The “two pandemics” are diverging. They will not sputter out at the same time. This divergence has practical consequences for imagining how and when the coronavirus pandemic will end.

Amy Rogers, MD, PhD, is a Harvard-educated scientist, novelist, journalist, and educator. Learn more about Amy’s science thriller novels, or download a free ebook on the scientific backstory of SARS-CoV-2 and emerging infections, at AmyRogers.com.

Sign up for my email list

Share this:

0 Comments