If you’re obsessing about vaccine risk, you’re missing the point

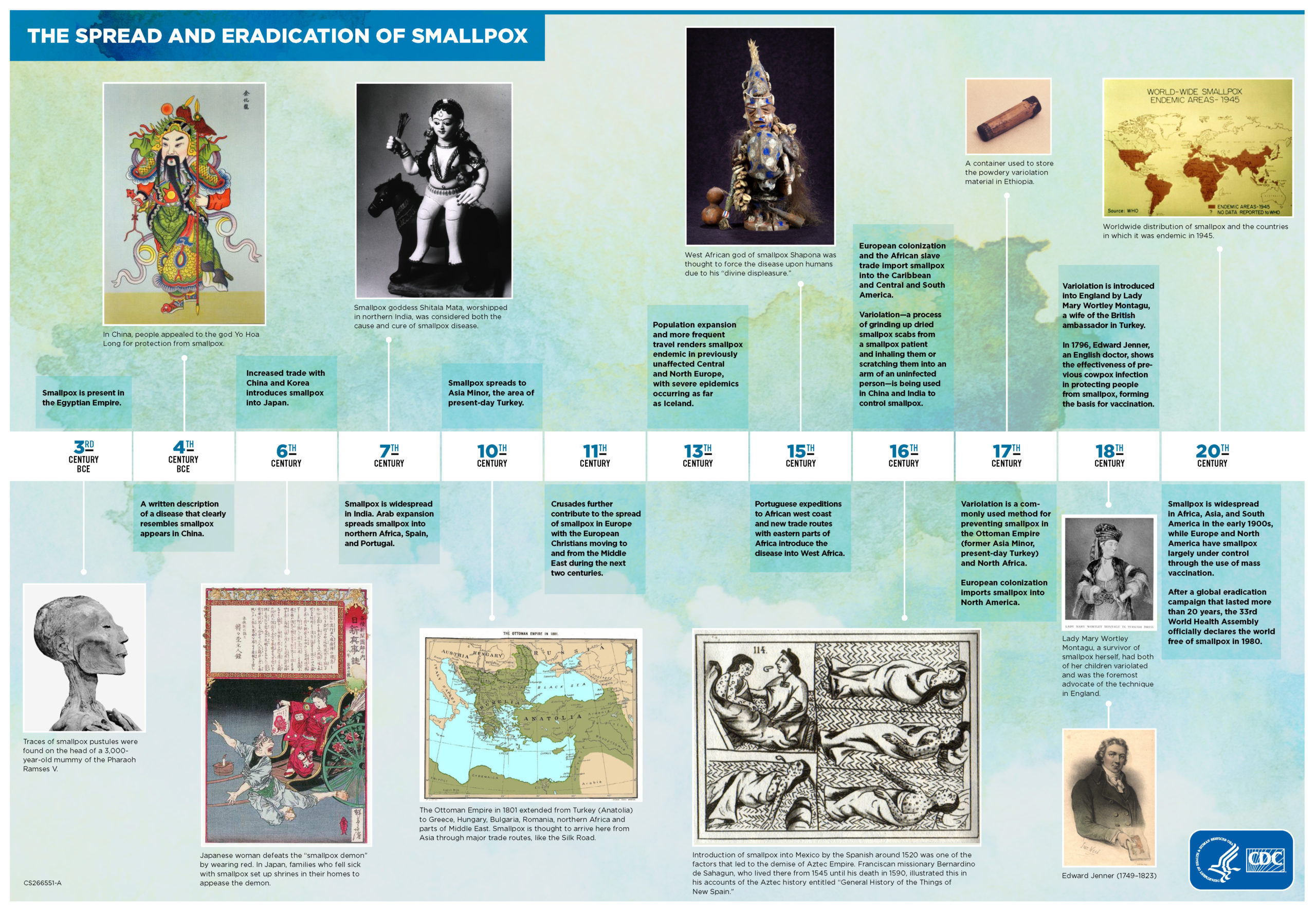

The history of smallpox, public domain image from CDC Public Health Image Library

I try to keep my finger on the pulse of online / social media conversations about the pandemic, and to respond to topics that are on people’s minds. This week I’m seeing more than ever an obsession with the particular details of vaccine risk. Short term. Long term. Risks of flu-like illness, blood clots, heart inflammation, infertility, body magnetism (!). Some of these are real (flu-like illness) and quantifiable (blood clots: 1 in a million with Johnson & Johnson vaccine). Others are completely speculative (infertility) or easily disproved (magnetism).

I started to engage in some of these conversations when it hit me: This conversation is pointless and frankly I’m tired of having it.

I don’t care if there’s a known, one in a million chance of a (temporary) clotting disorder after vaccination. I don’t even care if we don’t have data on long-term (years later) effects of vaccination.

The only thing that matters is whether vaccination is safer than natural infection by the coronavirus.

The smallpox story

We got lucky with SARS-CoV-2. In the grand scheme of airborne viral infections, it’s pretty gentle. Not like the Big Mother of All Pandemics: smallpox. Our collective memory of this scourge is dying off because the virus was totally eradicated by 1980.

“In the 18th century in Europe, 400,000 people died annually of smallpox, and one third of the survivors went blind. The symptoms of smallpox, or the “speckled monster” as it was known in 18th-century England, appeared suddenly and the sequelae were devastating. The case-fatality rate varied from 20% to 60% and left most survivors with disfiguring scars. The case-fatality rate in infants was even higher, approaching 80% in London and 98% in Berlin during the late 1800s.” Source: Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination by Stefan Riedel, MD, PhD

Smallpox risk was high, so people were desperate for protection–even if that protection came with its own risks. Variolation was a primitive precursor to modern vaccination. It was practiced for hundreds of years in the Middle East, India, Africa and China. Variolation was popularized in Europe in the early 1700s. (Great story, by the way, I encourage you to read the article.)

Variolation is

“the subcutaneous instillation of smallpox virus into nonimmune individuals. The inoculator usually used a lancet wet with fresh matter taken from a ripe pustule of some person who suffered from smallpox. The material was then subcutaneously introduced on the arms or legs of the nonimmune person.”

You read that right. They would take a sharp object, roll it around in the pussy discharge of some poor soul’s pox, and then stick it under the skin of a healthy person. Most of the time, that person would then get a minor, local case of smallpox in the vicinity of the injection. They might have a few scars in a place they could hide, and they would be immune to smallpox for the rest of their life.

It didn’t always work out that way.

“Although 2% to 3% of variolated persons died from the disease, became the source of another epidemic, or suffered from diseases (e.g., tuberculosis and syphilis) transmitted by the procedure itself, variolation rapidly gained popularity among both aristocratic and common people in Europe.”

Variolation directly and immediately killed around 1 in 50 of all people who took the treatment, and countless others died due to the other effects listed. Had the people of Europe gone mad? Why was this openly deadly medical procedure so popular?

Here’s the key:

“The case-fatality rate associated with variolation was 10 times lower than that associated with naturally occurring smallpox.”

It’s a pretty clear risk analysis. Smallpox was everywhere. At some time in your life, you’d probably get it. Did you want a 2% chance of dying (variolation), or a 20% chance (no variolation)?

And that’s my point. Vaccines are not recreational drugs. We don’t take them for fun. Anything you put in your body can have a bad effect. Even the most benign, most natural substance, like water or sugar, in some rare individuals, will cause a medical problem. (Examples: water in heart failure patients; sugar in diabetics or lactose-intolerant individuals). We take vaccines because there’s a virus out there.

Cure is not worse than the disease

Some of you may be saying, well, obviously smallpox was bad but COVID is no big deal for most people. That is true. Therefore vaccines against the coronavirus must be very, very safe. Nobody would take, and the FDA would never approve, a coronavirus vaccine as dangerous as the variolation procedure was.

Which brings me back to the active online conversations about vaccine risks. We want to know that vaccine risk is very low. Fortunately, the coronavirus vaccines currently approved for emergency use in the US are indeed very, very safe. We KNOW this because hundreds of millions of doses have been given, some of them over a year ago.

The problem is, the conversations seem to end with vaccine risk and ignore infection risk. So much effort and talk is expended to imagine, detect and quantify the rarest of vaccine side effects. So much speculation about what might happen years after a vaccine. But so little speculation about what might happen years after COVID infection.

We have good data from well-designed clinical trials of the vaccines over longer than one year. There is little or no reason to expect anything except very rare side effects over the long term. Granted, it’s not impossible. We truly cannot know until we do the experiment, so I would not get a COVID vaccine for fun.

We have good data that the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus can definitely cause rare side effects over the long term. (Source, Source, Source) This is pretty normal for viruses. Many viruses (most? all?) cause chronic symptoms, or trigger autoimmune disease, in at least some people. We expect that if a hundred million people catch the coronavirus, some thousands will experience side effects that linger long after the initial infection.

You can’t obsess on potential rare vaccine consequence unless you also consider the certainty of rare consequences from viral infection.

Risk vs benefit

We know that some people will have “long COVID.” Do we have actual data to show that the number and severity of these long-term effects is much worse than the number and severity of speculated vaccine effects several years hence? Honestly, no, because we haven’t done the experiment yet. But everything that we DO know points at the vaccines continuing to be safe for years after the jab, and the benefit of mass vaccination being much greater than the risk.

I believe this with my own body, and the bodies of my family. I take vaccine over virus.

Questions? Ask me.

Amy Rogers, MD, PhD, is a Harvard-educated scientist, novelist, journalist, and educator. Learn more about Amy’s science thriller novels, or download a free ebook on the scientific backstory of SARS-CoV-2 and emerging infections, at AmyRogers.com.